Key Takeaways

Only have a minute? Here are the salient points from the article:

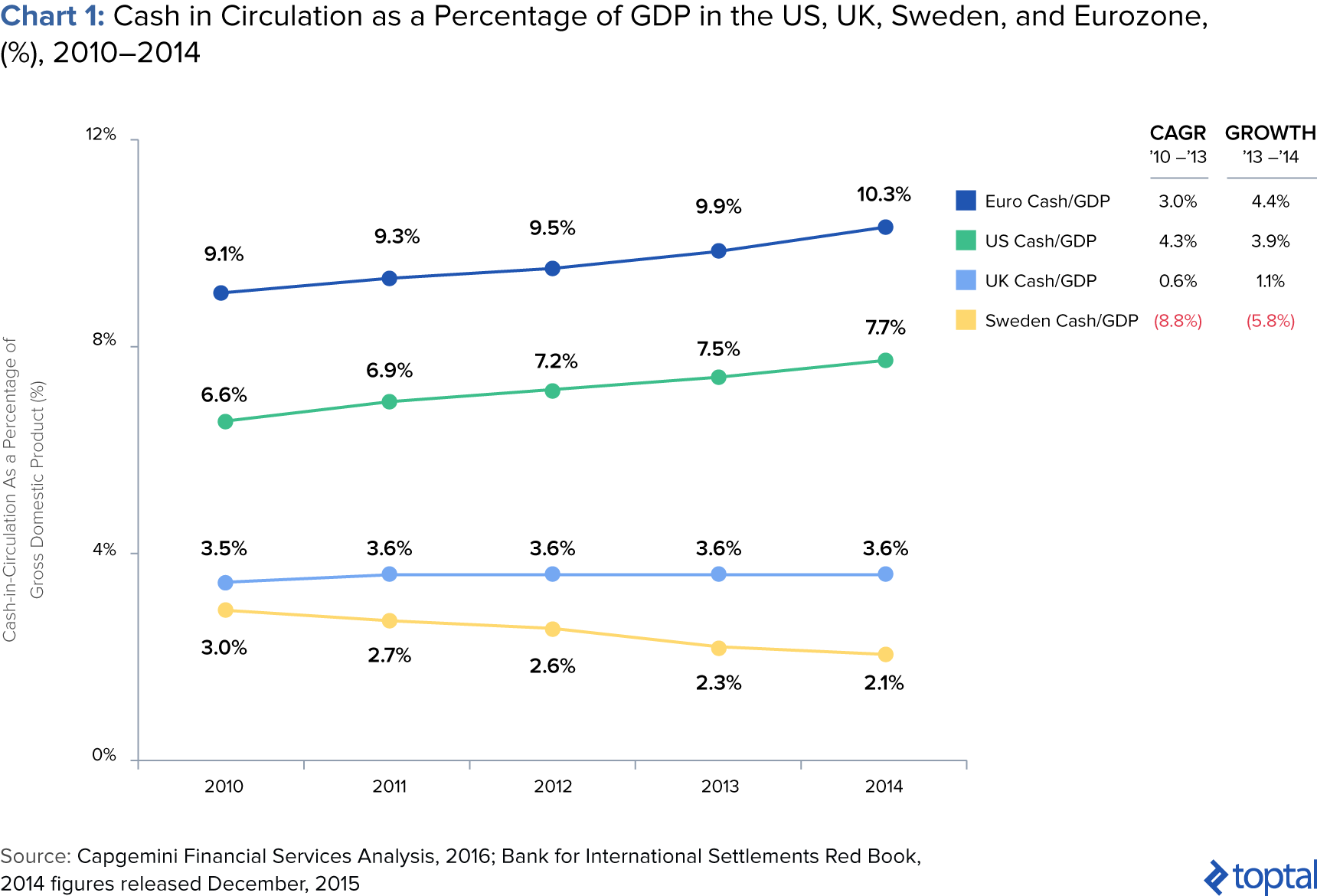

- Many countries (Sweden and India) and regions (EU) are adopting cashless habits or policies. Driven by “contactless” pay technology, increasing digital penetration, costs of using cash, and policy initiatives, the idea of a cashless society is no longer a figment of the imagination.

- In the near term, we are likely to witness a transition to less-cash societies, rather than a switch to cashless societies. Cash still accounts for 85% of total consumer transactions globally. Among established alternatives to cash, cards are the fastest growing payment instrument.

- Cashless economy pros: increased scope for monetary policy, reduced tax evasion, less crime and corruption, savings on costs of cash, and accelerated modernization of citizens.

- Cashless economy cons: potential violation of privacy, increased risk of large scale personal and national security breaches, and technology-dependent financial inclusion.

- Migrations to a cashless economy include considerations ranging from the purely financial, to those social in nature. Consequently, a country’s specific technological, financial, and social situations will inform its specific benefits, drawbacks, and approach to such a transition.

- Two case studies in the transition to cashless are 1) India, driven by a governmental digitization and demonetization measures, and 2) Sweden, driven by a high-tech culture and digital consumer habits. In Sweden, the government and central bank play facilitatory roles.

- Countries best positioned to go cashless include the US, the Netherlands, Japan, Germany, France, Belgium, Spain, Czech Republic, China, and Brazil.

Money is Technology. Will it Be Replaced?

From barter to cash to checks to online banking, money is an evolving technology that has been part of human history for thousands of years. While cash is expected to remain a significant payment instrument in the near future, factors such as “contactless” pay systems, increasing mobile penetration, and high costs of cash (ATM fees for individuals, cash storage for businesses, currency printing for governments, etc.) are prompting society to reconsider its ubiquity. Some experts support less-cash operations, arguing that high denomination notes should be phased out as smaller bills slowly fall towards disuse.

Others are more extreme, declaring a

war on cash and advocating for an outright ban on physical currency.

We conclude that we are likely approaching a less-cash future, not a completely cashless future. And, while progress has been made in this transition, it has hardly been universal or uniform. A migration to a cashless economy includes considerations ranging from the purely financial to those social in nature. Consequently, a country’s specific technological, financial, and social situations will inform its specific benefits, drawbacks, and approach to such a transition.

The following discussion of cashless societies pertains to a shift whereby physical cash is replaced by its digital equivalent. Money will still serve as a unit of account and store of value, but no longer as a physical medium of exchange. This piece delves into current global payment trends, the pros and cons of a cashless society, an analysis of country readiness, and case studies of India and Sweden.

Global Payment Trends

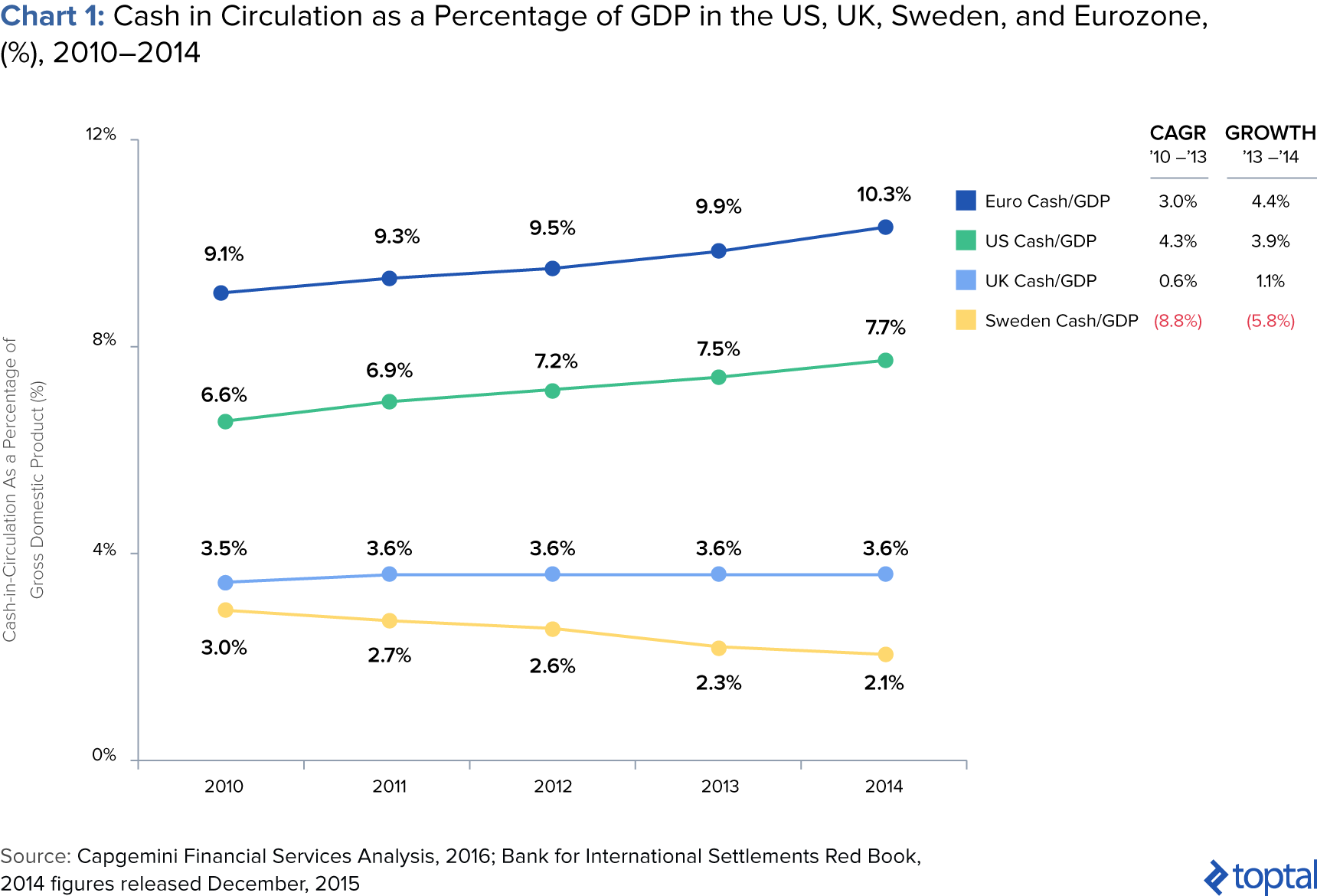

Despite adoption of digital payment methods, global cash use remains high. In fact, cash still accounts for

85% of all consumer transactions globally. Across the world, cash in circulation has remained stable, with the ratio of cash circulation to GDP even increasing across major markets. It continues to be resilient because it provides anonymity and universality to the payer. According to a

2016 report, cash is still expected to remain a significant payment method in the near future. However, services based on immediate payments are more efficient than cash and are expected to accelerate the move to digital payments.

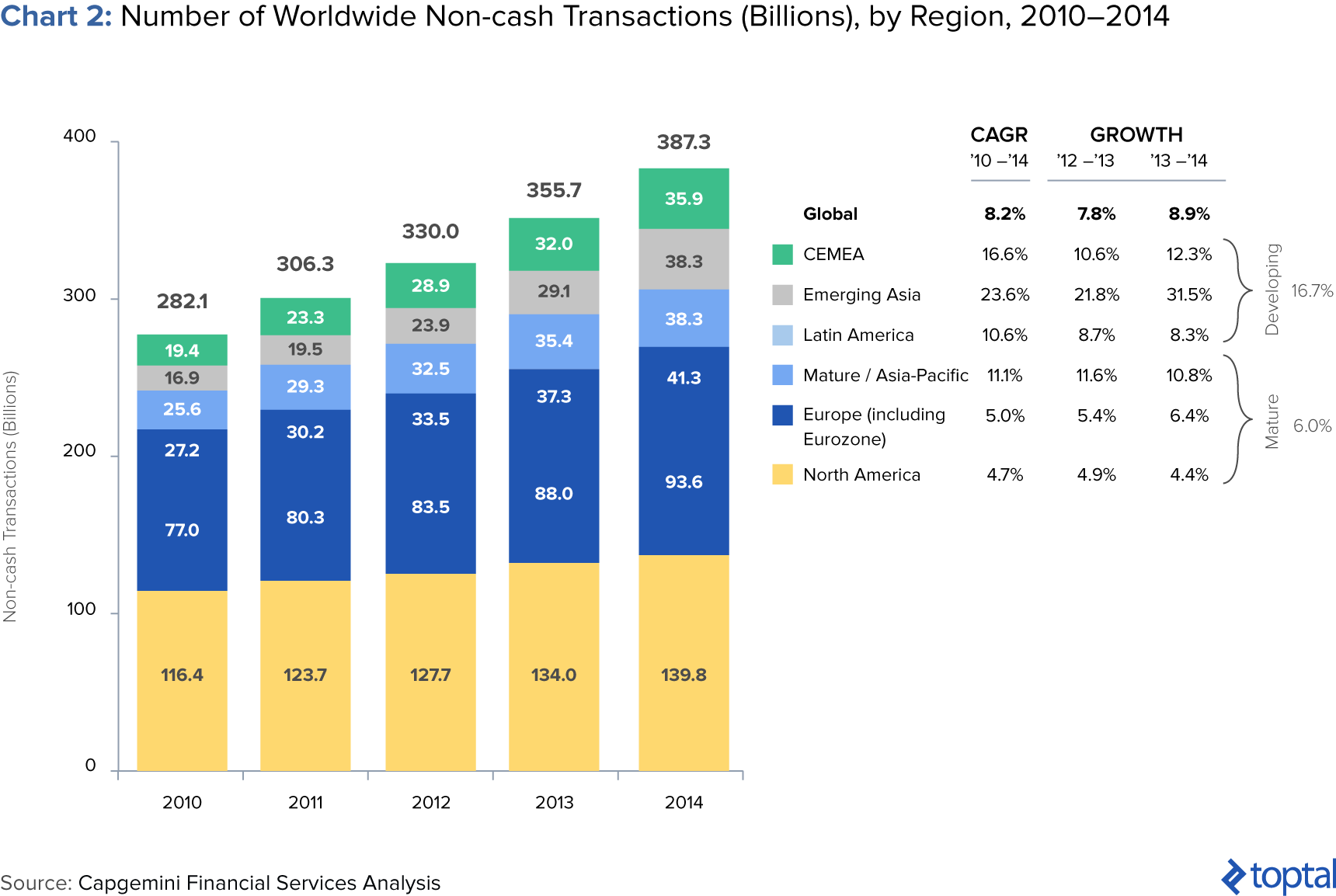

Global non-cash transaction volumes reached 387 billion in 2014, experiencing an unprecedented growth rate of 8.9%. This increase was primarily driven by close to 17% growth in developing markets, compared to 6% in mature markets.

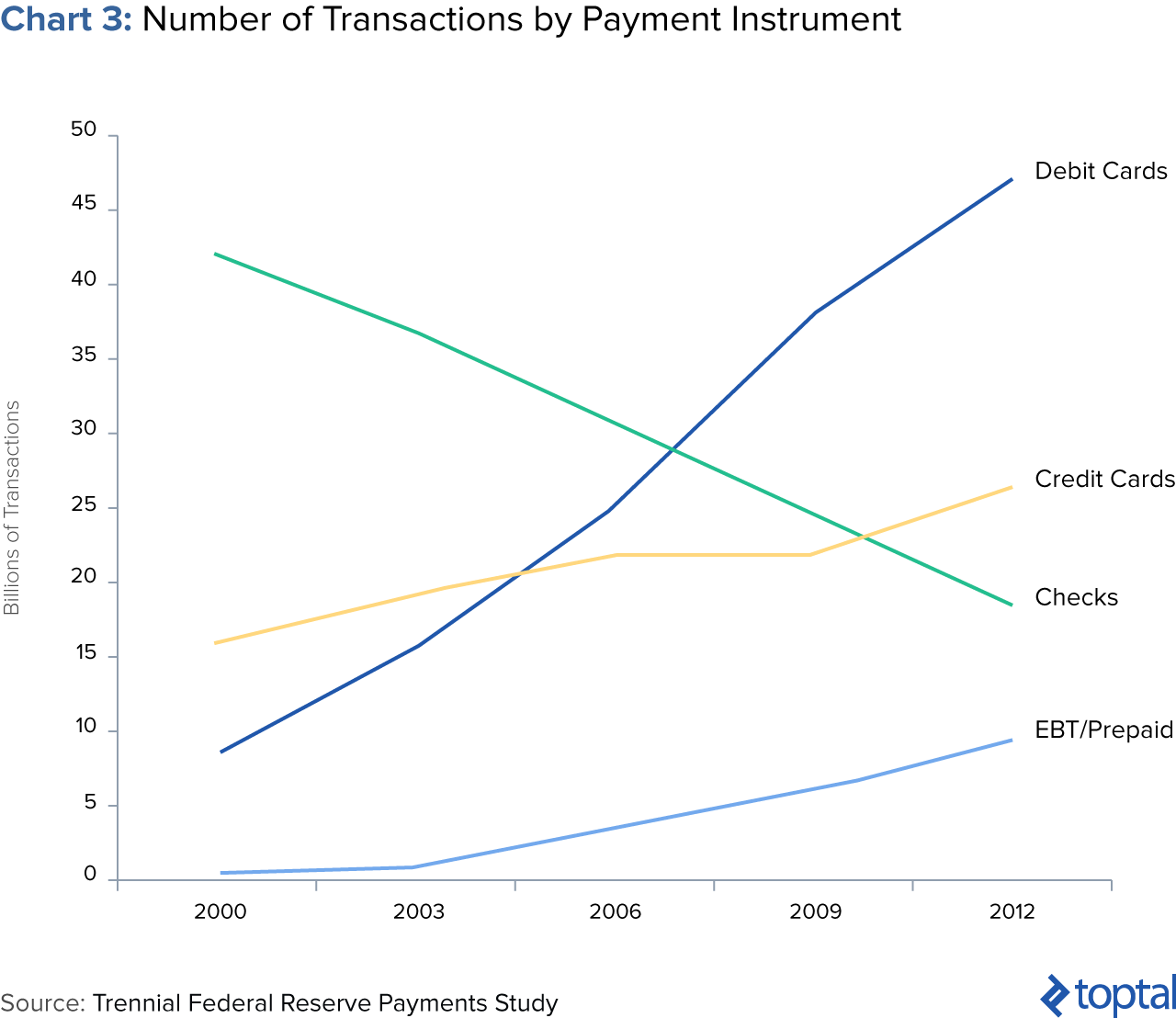

Among established alternatives to cash, cards—debit cards in particular—have been the fastest growing payment instrument since 2010. Meanwhile, check usage has declined consistently for the past thirteen years. More recently, the emergence of mobile card readers, electronic networks for processing large volumes of credit and debit transactions, and digitized private currency have threatened the prevalence of cash.

Though cash will remain prevalent for the foreseeable future, a migration to a cashless society is undoubtedly underway in certain countries. Sweden has long embraced cashless transactions, and the

EU has imposed restrictions on large cash payments. In 2014, China had the

fourth largest non-cash transaction market by volume, behind only the US, the Eurozone, and Brazil.

Financial analysts have

estimated that by 2020, eCommerce in China will be worth more than eCommerce in the US, the UK, Japan, Germany, and France combined. So, what are the drivers behind such a major shift?

Pros of a Cashless Society

Increased scope for monetary policy: In normal times,

people choose cash’s convenience (at a zero interest rate) over other safe assets offering higher yields. During economic downturns, governments have difficulty stimulating the economy by lowering interest rates, because people choose to hold cash instead. Therefore, due to the existence of paper currency, governments and central banks possess limited power to stimulate economic growth. This is known as the

zero lower bound theory.

However, in a cashless society, the inability of consumers to withdraw money from the financial system and store it in physical cash would provide governments and central banks with greater control of the economy through monetary policy. In particular, the unusual solution of a negative interest rate during economic downturns could more effectively be introduced. In a negative interest rate environment, people would

pay banks to store their deposits, instead of

earning interest on their deposits. This is intended to incentivize banks to

lend more. It is also meant to encourage businesses and individuals to invest, lend, and spend money rather than hoard it. In short, a cashless society would enable governments and central banks to more effectively utilize negative interest rates. If -0.5% doesn’t create enough stimulus, perhaps -1% will. If -1% still doesn’t do the trick, then perhaps -3%. In theory, negative interest rates do not have limits to how low they can go.

Carnegie Mellon’s Marvin Goodfriend argues in favor of negative interest rates, contending that they would allow central banks to independently pursue monetary policies to stabilize domestic employment and inflation.

Reduced tax evasion: Digital money and money services would bring about increased transparency in transactions, providing governments with enhanced abilities to track and analyze citizens’ financial activities. Ultimately, this would decrease tax evasion and increase tax payouts to the government. A 2016

study conducted by the nonpartisan Centre for Studies in Economics and Finance (CSEF) studied the effects of electronic payments on tax evasion in Europe. CSEF found that the use of electronic payments such as debit and credit cards reduced tax evasion, and that there was a positive statistical relationship between cash withdrawals and tax evasion.

Though difficult to pinpoint, experts estimate that the tax evasion amounts to between

$100 billion and

$700 billion a year in the US The IRS

estimates that in 2006, taxes not paid voluntarily were over $450 billion, with a gap of $385 billion still remaining after tax collection efforts. These costs would be even higher in Europe, where tax rates are even higher.

Less crime in black markets: The anonymity and untraceability of paper currency facilitates the operations of corrupt activities. In a cashless society, the elimination of this medium of exchange would disrupt their normal operations and force them to rethink their business models. As

Peter Sands writes for the Harvard Kennedy School, without high denomination notes, those engaged in illicit activities would face higher costs and greater risks of detection.

The size of the black market, or shadow economy, is substantial. Estimates of its size in the US start at around

8% of GDP. In Europe, where taxes are higher and regulation more onerous,

estimates suggest that the size of the underground economy is considerably larger than in the US.

According to

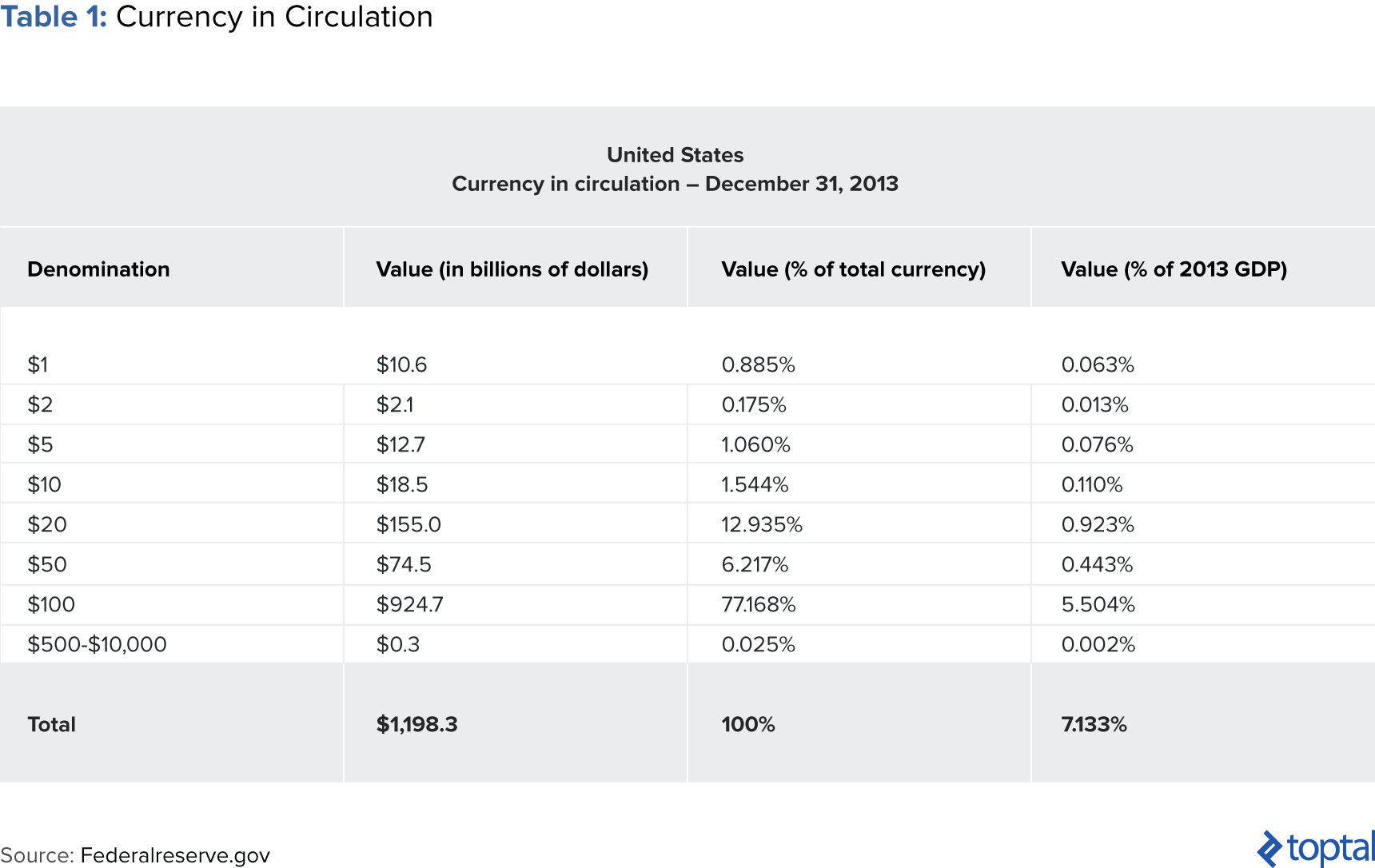

Harvard economist Kenneth Rogoff, there is an enormous difference between the amount of currency most OECD countries have in circulation, compared to the amount that can be traced to legal usage in domestic economies. Currency not in the domestic legal economy or in the global economy is mainly in the the domestic underground economy. As of March 2013, there was $1.3 trillion US currency in circulation. This translates to around $4,000 for every man, woman and child living in the United States. Further, nearly 78% of the total currency value was in $100 bills, meaning more than thirty $100 bills per person. By contrast, denominations of $10 and under accounted for less than 4% of the total value of currency in use.

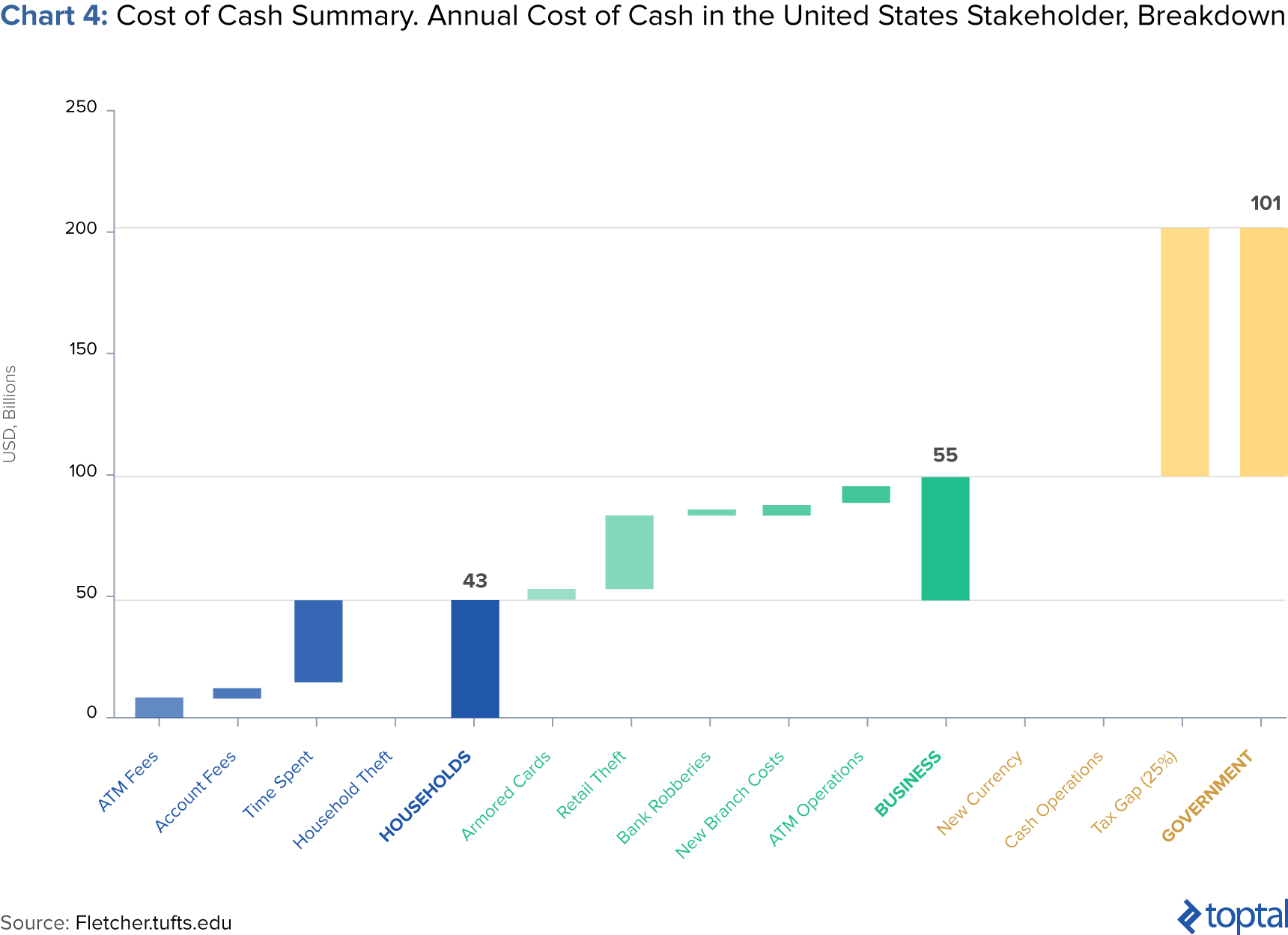

Savings on costs of cash: Nations can benefit from the shift to cashless transactions by saving on the cost of cash. These costs of cash include ATM fees for individuals, cash storage and transportation expenses for businesses, and currency printing costs for governments. According to

research conducted by the Tufts Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, the aggregate cost of cash in the US is $200 billion annually. The estimated cost of cash is

MXN 3-6 billion annually in Mexico, and

over Rs 200 billion annually in India.

Proponents claim that cashless transactions and elimination of cash costs can be advantageous for poor individuals and small businesses. These are the parties for which the costs of cash are

disproportionately borne. For individuals, cash imposes a

regressive tax and impacts the unbanked the most. The unbanked pay four times more in fees to access their money than those with bank accounts, and are at five times higher risk of paying cash access fees on payroll and EBT cards.

For businesses, paper currency must be stored, guarded, and accounted for. Mom-and-pop stores, many of which operate in poor neighborhoods and rural areas, often cannot afford security and cash transportation services. Removing cash from the equation could result in savings for the marginalized. As The Fletcher School’s Bhaskar Chakravorti

declares, “It is time we acknowledged the cash paradox: While cash may be considered the poor man’s best friend, it also places a disproportionate burden on the poor.”

Fostering the adoption of new wireless technologies: A cashless society could accelerate the path to digitization, pushing those who might otherwise be reluctant—or previously have no need—to modernize. According to the

McKinsey Global Institute, digital finance could provide an additional $2.1 trillion of loans to individuals and small businesses as providers gain improved abilities to assess credit risk for a larger pool of borrowers. Financial services providers would also benefit from a shift from traditional to digital accounts, potentially saving $400 billion annually in servicing fees.

Cons of a Cashless Society

In addition to myriad potential benefits, this transition might be accompanied by several drawbacks:

Violation of privacy: In a cashless society where all money, payments, and money services are digitized, there is concern around “big brother” surveillance activities by the government and organizations seeking to profit from the traceable data. Some opponents of cashless societies view the ability to take one’s ability to spend cash anonymously as central to freedom within society.

Elaine Ou, former lecturer at the University of Sydney, equates a cashless society with the surrendering of individual monetary control to financial institutions. As she articulates in her

editorial, “A world without paper money is a world without money. Money belongs to its current holder. It doesn’t matter if a banknote was lost or stolen at some point in the past. Money is

current; that’s why it’s called currency! A bank deposit, however, grants custody of money to the bank. An account balance is not actually money, but a claim on money.”

Importantly, a claim on money means that every transaction in a cashless society would have to pass through a financial gatekeeper. If banks and other private institutions hold our money, they would also have the right to refuse transactions at their discretion. Inevitably, then, certain payments would not be given due process. After all, previous attempts to prevent money laundering have sometimes resulted in the removal of financial services access for legitimate

individuals,

businesses, and

charities.

Increased risk of security breach: A cashless society may bring about increased risks to personal and national security. From a personal security standpoint, the risks we already experience when we lose credit cards or our phones would only be exacerbated in an environment without paper currency. Today, becoming a victim of digital hackers can lead to

denied payments, identity theft, account takeover, fraudulent transactions and data breaches. These risks would still exist in a cashless society, though the volume of cashless transactions and points of exposure for the average consumer would be much higher. What’s more, without cash reserves in households and businesses, a cyber attack or computer malfunction would leave consumers without a safety net.

From a national security perspective, during financial and global crises, cash has repeatedly demonstrated its importance for consumers and members of society. During the financial crisis of 2008, cash provided a

safe haven for consumers. For example, the Australian Reserve Bank experienced a

12% rise in demand for cash in late 2008 in response to the financial uncertainty.

Decreased financial inclusion: While some experts, as mentioned previously, believe a shift to cashless transactions could eliminate the costs of cash for the marginalized, others believe this shift would exacerbate the existing issue of financial inclusion. While utilizing cash is direct and simple, moving to a cashless society would place pressure on these individuals to sign up for formal financial services, something the poorest might be unable to do.

In developing countries,

2.5 billion people do not have access to traditional financial services. Traditional banking infrastructure struggles to serve low-income customers, particularly in rural areas. The issue of financial inclusion also extends to modern countries: in the US and Western Europe, nearly

70 million and 100 million are unbanked, respectively.

A method of combatting these effects is the promotion of mobile connectivity. According to

research published by GSMA, mobile phones and mobile banking have been powerful tools for bringing access to payments, transfers, credit, and savings to unbanked people. In conjunction with governmental support and incentives, mobile is uniquely positioned to overcome the challenges of payments: It provides a platform to combine digital identity, digital value, and digital authentication for

low-cost access to financial services.

While it may seem counterintuitive for developing countries to have high mobile money services usage, many off-the-grid families and small businesses own basic mobile phones with alphanumeric keypads and black and white display. Another enabling factor includes regulators, who are increasingly recognizing the role that non-bank providers of financial services can play in fostering financial inclusion. Consequently, they are establishing more enabling regulatory frameworks. In

47 out of 89 markets where mobile money is available, regulation allows banks and non-banks to provide mobile money services in a sustainable way. In addition, it would be helpful for governments to promote access to financial services or the technology necessary for the services as a public good, just as it does with education and water.

Currently, 255 mobile money services are now live across 89 countries, and the number of registered mobile money accounts globally also grew to around 300 million in 2014. Globally, there are now fifteen countries with more mobile money accounts than bank accounts, indicating that mobile money is a key enabler of financial inclusion.

A successful example of mobile in emerging markets is M-Pesa, which is transforming the financial landscape in Kenya. Launched in 2007 by large mobile network operators, the service allows users to deposit money into an account stored in their cell phone, to send balances via SMS text messages to other users, including retailers, and to redeem deposits for cash. It is considered to be a branchless banking service, whereby customers can withdraw and deposit money with an extensive network of agents that act as banking agents. In 2014, there were

81,000 M-Pesa agents in Kenya alone. To better understand the penetration of the service, consider the following: M-Pesa is used by

17 million Kenyans, equivalent to more than two-thirds of the adult population, and around 25% of the country’s GDP flows through it. M-Pesa has

also launched in India, Albania, Romania, and multiple African countries.

The above benefits and drawbacks can help us understand the reasoning behind a country’s decision to go cashless, or the timing at which a country may go cashless. Let us now examine which countries are currently best positioned to adopt cashlessness.

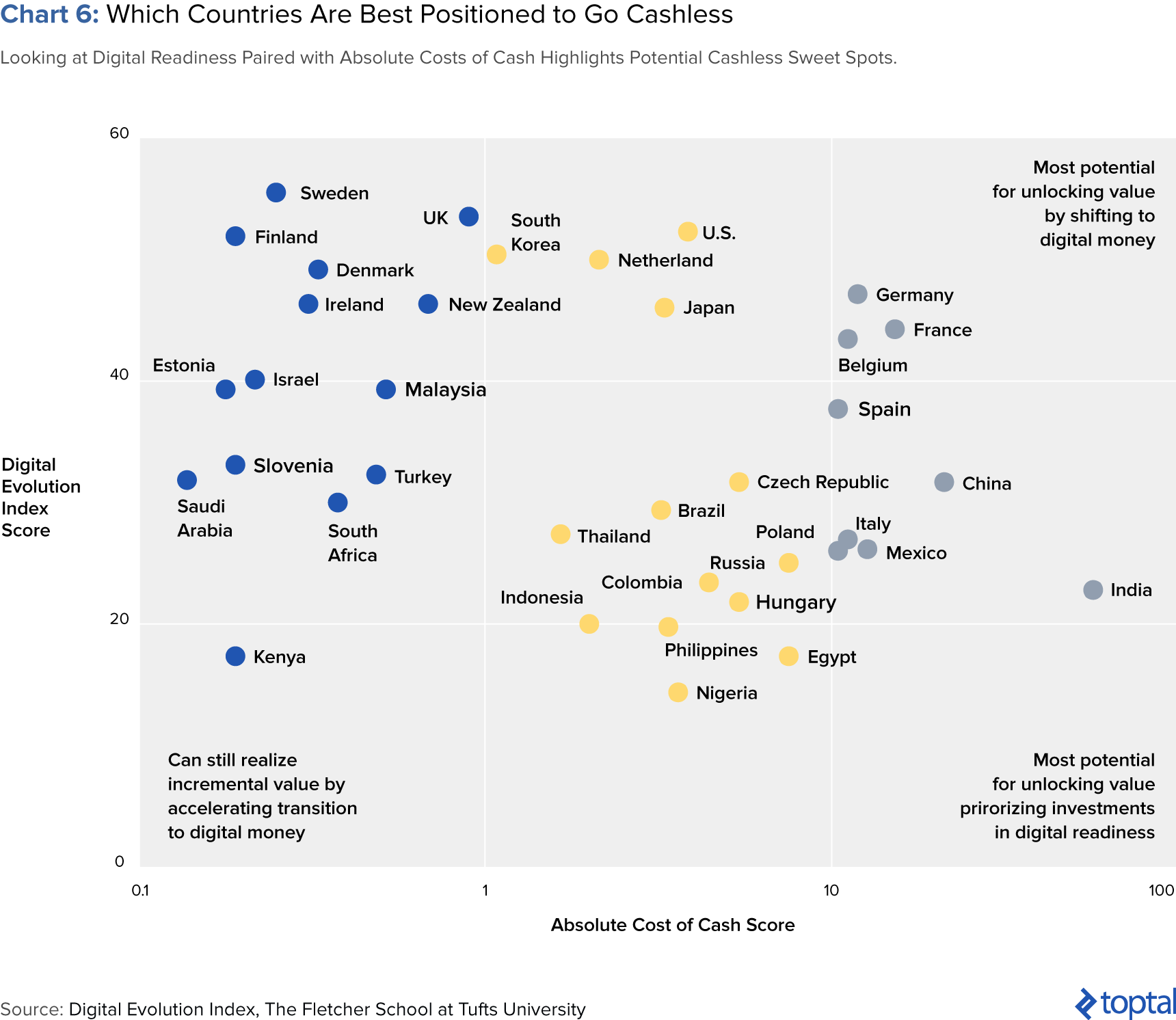

Which Countries Are Best Positioned to Go Cashless?

According to the

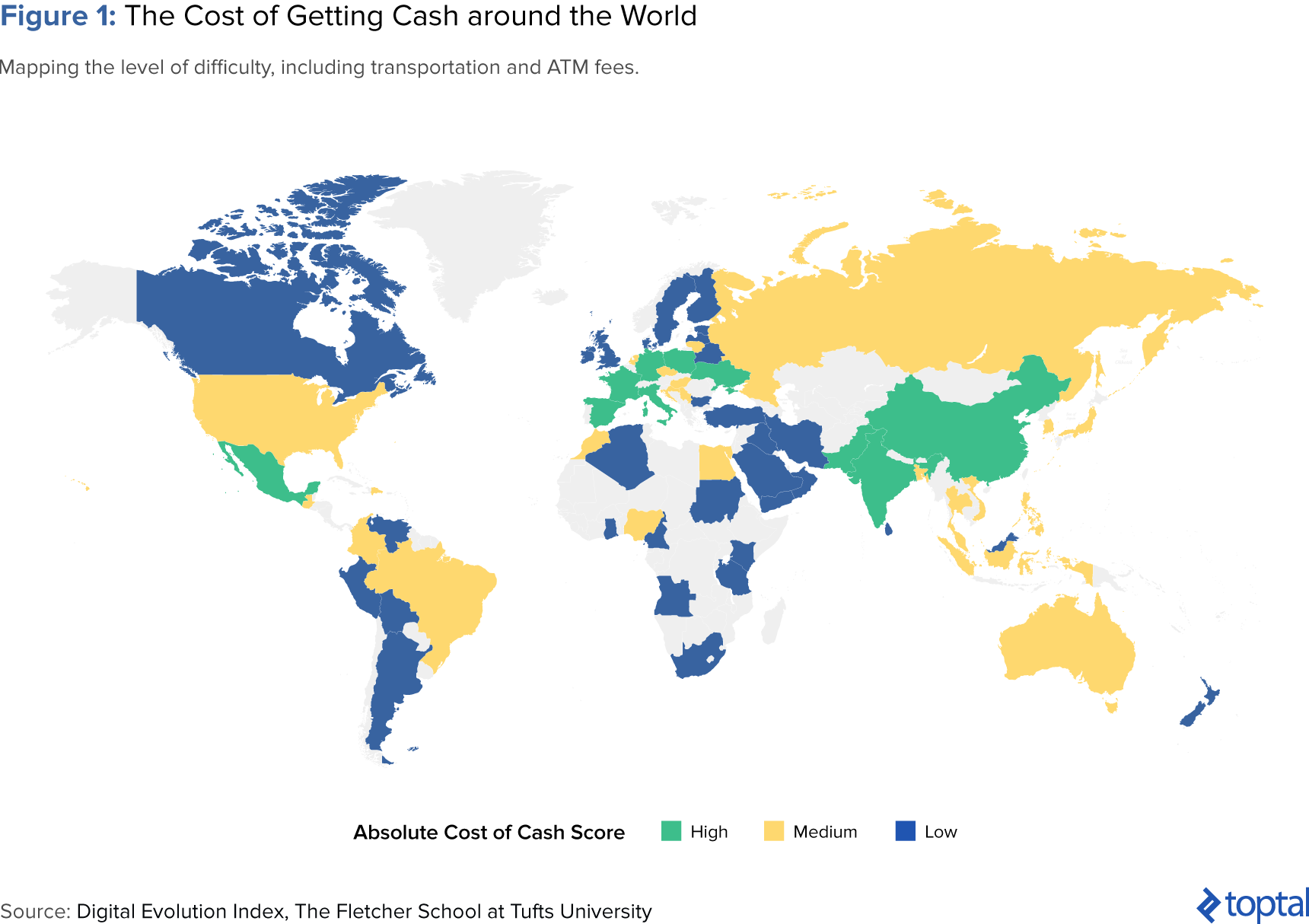

Harvard Business Review, the first major consideration is the aggregate cost of cash, which will identify the countries with the most to gain from the change. The cost of cash is derived from: 1) The cost of ATM maintenance for banks, 2) Cost of cash to consumers, including the costs of obtaining cash, such as transport to ATMs and ATM fees, and 3) The tax gap, which is the estimated amount of tax money owed to the government but goes uncollected or unreported due to cash transactions.

The map below represents these aggregate costs of cash. A caveat in its interpretation: Countries indicated with “low” costs are not necessarily closer to being cashless societies. The map simply indicates that the costs of cash in these countries are relatively lower than other countries.

Here is a breakdown of cost of cash categories, borne by different parties:

- ATM maintenance costs borne by banking institutions: These are disproportionately high in many parts of the developing world, such as sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America. It is also high in geographically large, sparsely populated countries, such as Canada, Russia, and Australia, where there are many logistics challenges.

- The absolute cost of cash to consumers: These costs are high in some of the world’s most populous countries, including Indonesia, Nigeria, Bangladesh, India, China, and the United States. They are high in many of the major European countries, such as Germany and France, as well as in Japan. These costs are lower in several Scandinavian countries with relatively entrenched mobile payments systems, such as Sweden, Finland, and Denmark, as well as countries with rapidly evolving mobile payment systems, such as South Korea and Kenya.

- Tax gap as a cost to governments: Tends to be higher in emerging markets, where shadow economies tend to be larger. In India, for example, the tax gap could be as large as two-thirds of overall taxes owed. The larger the tax gap, the more the country has to gain from a migration to a cashless economy.

The second major consideration in determining a country’s readiness is its level of digital advancement and infrastructure. Developing countries in Asia and Latin America are

leading in momentum. They also benefit from ongoing investment, remaining attractive destinations for startups and for private equity and venture capital. On the other hand, most Western and Northern European countries, Australia, and Japan have been slowing down in momentum.

Based upon these factors, the US, Netherlands, Japan, Germany, France, Belgium, Spain, Czech Republic, China, and Brazil have the greatest potential for unlocking value by policy and innovation led migration to a cashless society.

Clearly, various regions have different benefits to consider and are at varying levels of readiness for a cashless economy. The following section details case studies of two countries already experiencing such a transition. The first country we explore is India, whose transition has largely been propelled by the government. The second country we examine is

tech-forward Sweden, which has experienced a more natural progression towards a cashless society, prompting the Swedish government’s role to be more of a facilitator.

Spotlight on India’s Demonetization Campaign

India is an interesting case study because of its historical reliance on cash and its lower digital evolution index. Yet, it stands to benefit significantly with regards to financial inclusion, corruption, and relatively high costs of cash. Interestingly, much of the transition has been initiated and driven by the government through both voluntary and involuntary measures. It seems, then, that the Indian government believes the benefits of a cashless society significantly outweigh its potential issues.

A shocking mandate occurred in November 2016, when India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi made a surprise public address via live television. He announced that after 50 days, all 500 ($7.50) and 1,000 ($15) rupee notes, representing 86% of the currency in circulation, would

cease to be legal tender. While citizens were permitted to exchange 500 and 1,000 rupee notes for higher denominations, the

government prohibited individuals from exchanging more than 4,000 rupees ($60) at a time.

Prior to the announcement, over 95% of India’s transactions were cash, 90% of vendors did not have means of accepting electronic payment, and nearly half of the population did not have bank accounts. Modi’s ostensible motivation was to reduce corruption, believing that these high denomination notes were used to finance terrorism, fund illegal drug sales, fuel the black market, drive counterfeiting, and pay bribes. Since the announcement, however, the claimed objective of the exercise has

transitioned from rooting out black money to modernizing the Indian economy.

Modernization has been a priority for the Indian government in the last decade, during which it has taken several measures to accelerate digitization. In 2009, the government launched

Aadhaar to improve digital identity. Then, to provide citizens with bank accounts, the government sanctioned the launch of

11 payment banks, offering incentives to open accounts. When the United Payment Interface

launched in 2016 as a way for banks to transfer money directly to one another, the Reserve Bank of India advocated for it. After the demonetization announcement last year, the government introduced incentives for digital purchasing, including discounts on petrol, diesel, and railway season tickets.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the controversial demonetization policy has been met with both

pointed criticism and

praise. Here are a few details regarding the results:

Effects on citizens: In the immediate aftermath of the announcement,

chaos erupted. Long lines formed at ATMs and banks, and altercations broke out as people waited for hours (sometimes for over twelve hours). Often, repeated trips to the bank were necessary. Banks, which also had not been notified of the change, did not have enough of the high denomination notes for the masses looking to redeem their canceled notes.

Monishankar Prasad, a New Delhi-based author,

pointed out that the unbanked citizens and the poor were taken off guard. Without access to structural resources, these people were hit hardest.

University of Pennsylvania’s management professor Mauro F. Guillen, however,

argues that the long-term benefits outweigh the short-term costs: “In the short term, [the move] could stifle some businesses that are legal and clean, if they use cash payments. But everyone will adjust. And while it can hurt some small businesses and individuals, it is better to do it than not.”

Effects on corruption: It was originally thought that the shadow economy would not be able to exchange or deposit their illicitly-obtained wealth. Theoretically, by having canceled banknotes going unredeemed, the Indian government would then

add a large sum of assets on the balance sheet, an amount estimated to be $45 billion. However, even with strict limitations around banknote exchanges, the black market was

still able to unload much of their money. It is still being investigated as to how they were able to achieve this, but it seems a variety of tactics were utilized, including

cutting deals with corrupt bankers, threatening bank officials, or utilizing

inactive bank accounts. India’s Enforcement Directorate has been investigating bank branches throughout the country.

While experts acknowledge that the move could create a temporary obstacle in black economy operations, many question its efficacy as a long-term solution. They

assert that certain trades and areas cannot be digitized just by willing it.

Others warn that it is only a matter of time until the black market utilizes alternative financing techniques such as the US dollar or the pound sterling.

Effects on digitization and modernization: As expected, Modi’s demonetization campaign has proved to be a boon for the country’s e-payment providers. For example,

Paytm reported a 3x surge in new users while

Oxigen Wallet’s daily average users increased by 167% since demonetization began.

Market and political response: The market has downgraded India’s growth in the short term, but is optimistic that they will be outweighed by the long-term benefits. In December 2016, S&P Global Ratings

decreased its estimated economic growth rate for 2016-17 by one full percentage point to 6.9% to reflect the disruption. However, Dharmakirti Joshi, Chief Economist of Crisil, a subsidiary of S&P Global, noted that, “We expect lower private consumption in fiscal 2017, but expect demand to revive and growth to rebound in fiscal 2018. India should shortly revert back to an 8% annual growth trajectory.” The Wall street Journal similarly comments that while GDP growth slowed as a result of the demonetization policy, “India is expected to

remain one of the world’s fastest-growing large economies.”

In addition, the March 2017 victory of the BJP party, of which Modi is a part, is

viewed by some as an endorsement of Modi’s groundbreaking demonetization policy. The

stock markets rallied at the prospect of the BJP victory. The next trading day, the Bombay Stock Exchange Sensitive Index (Sensex) shot up 496 points (1.71%). The National Stock Exchange 50-share index also closed at more than 9,000 for first time in history.

Spotlight on Sweden

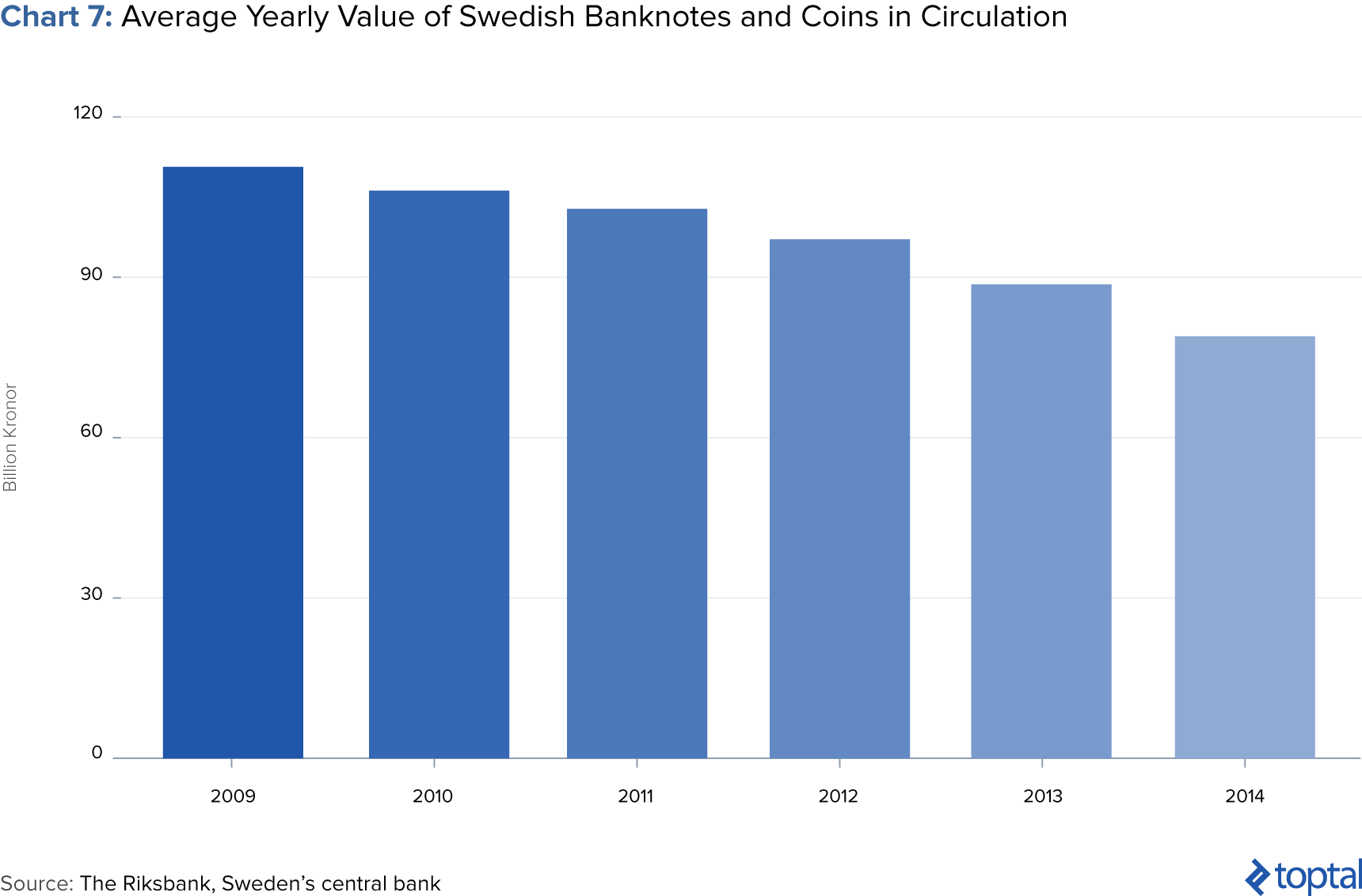

Next, we move onto Sweden, a country with lower costs of cash and

advanced digital infrastructure. Unlike India, consumers’ habits and the markets have largely dictated the transition to a cashless society, with the government and central bank (Riksbank) helping to facilitate the change. Sweden is also one of the first countries to

adopt a negative interest rate, leveraging its citizens’ cashless preferences to stimulate the economy.

The Swedes are notorious for their embrace of technology and cashless transactions. Swedish buses and the Stockholm metro do not accept cash, and retailers are legally entitled to refuse coins and notes. Street vendors and even churches increasingly prefer electronic payment. Hooked on the

convenience of digital money, cash transactions made up a mere 2% of the value of all payments in Sweden last year. In shops, cash is now used for less than 20% of transactions, half the number five years ago and significantly below the global average of 75%. When it comes to alternative payment methods, Swedes use cards

three times as often as the average European, yielding an average of 207 payments per card in 2015. Preferring to pay digitally, Swedes have low demand for cash, which is dropping at a rate of

20% a year. As a result, about

900 of Sweden’s 1,600 bank branches no longer keep cash on hand or take cash deposits. Cash machines are being dismantled, especially in rural areas.

Circulation of the Swedish krona has fallen from around 106 billion in 2009 to 80 billion last year.

Taking note of its citizens’ preferences, the central bank and other major banks

jointly created the popular digital wallet Swish to enable payments between bank accounts in real time. Riksbank’s involvement in Swish’s creation and the credibility it lends to the service, has been critical to Swish’s success. Swish is now used by close to

half of the Swedish population. In addition, capitalizing upon its citizens’ embrace of technology and cashless transactions, Sweden is one of the first countries to have its central bank adopt a negative nominal interest rate. Earlier this year, in a continuous battle against deflation, the Riksbank

held its nominal interest rate at negative 0.5% and stressed chances of further cuts. Although retail banks have yet to utilize negative interest rates, it may only be a

matter of time until they do so.

For individual consumers, the move towards cashlessness has led to a number of complex issues. Last year, the number of

electronic fraud cases reached 140,000, which represents more than double the amount more than a decade ago. In addition, there is concern that the ease of electronic payments in combination with negative interest rates are driving soaring debt burdens. Their fears are not unfounded, as Swedish household debt is at an

all-time high, with the average Swedish household debt to disposable income metric at a

record high of 180%. Sweden is also currently experiencing a housing crisis; money is so cheap to borrow that the Swedes are

funneling cash into property.

Critics also point to

concerns that pensioners in Sweden who use cash may be marginalized and excluded; only 50% of Swedish National Pensioners’ Organisation members use cash-cards everywhere. Perhaps for these reasons, cash is not dead—Swedish central bank Riksbank predicts it will decline quickly, but will still be circulating in twenty years.

The Paths to a Cashless World Are Many and Varied

A cashless society is no longer just a figment of the imagination. While cash still reigns globally on aggregate, progress towards cashlessness is particularly pronounced in specific countries. Additionally, it is clear that there is no “one size fits all” blanket solution for such a major shift. Because the migration involves technological, financial, and social considerations, we can expect each country to select an approach according to their unique positioning and capabilities.

Regardless of approach, the transition to digital money and money services will have profound implications on some of the most basic aspects of society. This great change presents opportunities for governments to improve issues surrounding income inequality and poverty, and opportunities for entrepreneurs to create innovative, disruptive businesses.